Post by: Grant Rodiek

Creative nerds everywhere want to be entrepreneurs. Thanks to Kickstarter, the Internet, and money growing on trees, it’s now relatively possible for these nerds to become entrepreneurs.

I am not a publisher, but I want to be. Badly. Yes, I self-published Farmageddon and yes I’m self-publishing Battle for York. The distinction I wish to make is that I did these as a creative exercise. I did these for myself. I believe a publisher creates games for the purpose of revenues and profits. A publisher does it to be a business. I did it for funsies. Now, that doesn’t mean a publisher doesn’t have fun and doesn’t love games, but to be successful, my games need to make money and I’m not quite there yet.

This article is intended as a case study to stir discussion and aid those interested in game publishing. I receive quite a few emails with questions about publishing and I do my best to answer them with what (little) I know. I’ve been taking notes for years and watching. This article will discuss the development I did to publish Battle for York, what I would have done differently if this were a real, profit-focused print run, and the marketing ideas I have for the game. In summary, you’re going to read about what I did, what I would have done, and some of my goofs.

Development: The Actual

Overall I’m quite pleased with the development of Battle for York. Some of my friends have told me that they tested their game a few times, a publisher signed it, then they were hands off for the next year’s worth of development. Well, I did that development. York was thoroughly tested over the course of a year with friends and co-workers, non-gamers, gamer gamers, random folks at GenCon 2012, folks at Protospiel Milwaukee, and a few folks in the Prototype Penpal Program.

Testing overall went through 3 main phases: mechanical, balance, and usability. The first phase focused primarily on making the game work. Getting it to an Alpha state. The second phase focused on making sure the game was fun and fair. Also, to ensure it’s fun to play 1, 5, 10, and 20 times (it is!). This phase is about getting it to a Beta state. The final phase was about making sure the game was as easy as possible to learn and play. It was about ensuring the reference boards and cards presented the information as well as possible. I haven’t done this for a game before and I found it insanely useful.

All told, the game has over 70 tests with dozens of people. It was tested extensively with 4 peers for the sake of deep, long-term balance testing. The rules have also been read, tweaked, and massaged for the entirety of this year. I write my rules at the beginning of the project for precisely this reason. I am reasonably confident my rules are good.

Development: The Potential

If this game had more of a development budget I would have done a few things differently. As it stands now, I had one local long-term test group and one blind long-term test group. I would have sent out copies to at least 2 more groups for long-term blind testing. This would have been invaluable for balance and accessibility. Plus, more word of mouth marketing.

I also would have tried to work out a testing moment with a prominent reviewer. Now, this might not have occurred — reviewers are busy and reluctant to do these things. I would have been willing to pay them for their services, services being 2-5 tests. I would do this in the hopes of getting a private, mock review. I would want to make sure it would go over well in the review circuit. Now, I cannot guarantee every reviewer would agree with the mock review, but testing with 1 or 2 is a good sample size. Hint: We do this all the time in the digital game space. It’s very useful.

Another change is that I would have begun stalking local FLGS to attempt to get some local word of mouth built. There are a few good stores near me: Gamescape in SF, End Game in Oakland, and Black Diamond Games in Concord. However, doing this takes time, gas money, and the stores need to be cool with me testing/shilling my game on their premises. This isn’t just a show up and rock it affair, so it would need some effort.

Finally, I would have hired a dedicated editor to examine my rules. I would not change the number of peers who examined them. Their service has been amazing and again, the rules are good. But, paying someone who is on the line to make it awesome is a good thing to do. This maxim is so true: you get what you pay for.

If you’re curious about the design side of Battle for York, ask questions, or check out this lengthy post I wrote on its origins and development.

Art: The Actual

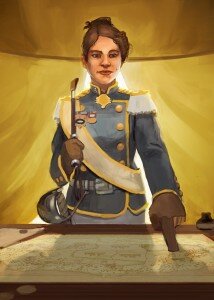

I’m very pleased with the final art for Battle for York. The cards were illustrated by one of my favorite artists, John Ariosa. The work he created was amazing, working with him was fantastic, and overall I’m just thrilled. Here are some of his pieces:

I wrote about working with artists earlier, but I’ll rehash some of the info. I spent a year thinking about the art for York and built not one, but two Pinterest boards for it: Theme 1 and Theme 2. I had a clear vision and that really helped things.

I also greatly scoped down the required assets to fit within my tiny budget and John’s time frame. Ultimately, I hired him to create 5 images, each done in 4 colors. I asked for characters with simple backgrounds, which also kept things within scope.

I also hired Robert Altbauer from the Cartographer’s Guild to illustrate a map for me. I discussed the project with 3 artists, but ultimately settled on Robert because of his style and experience, his demeanor, and his very reasonable quote. I had him create 2 maps: 3 player and a 2-4 player. These were based on drawings I created for the prototype — the layout was refined and complete. He made it pretty and created icons for it, including the Cities, Seaports, Forts, and Headquarters. You can see one of his maps with the board elements here:

I handled the graphic design duties for the project, which included icon sourcing and layout. For icons, I used Game-Icons.net and modified them as needed, usually just by simplifying the icon or modifying it to fit the aesthetics of the rest of the game. These icons are consistently created and provided free within the creative commons license, so I used them.

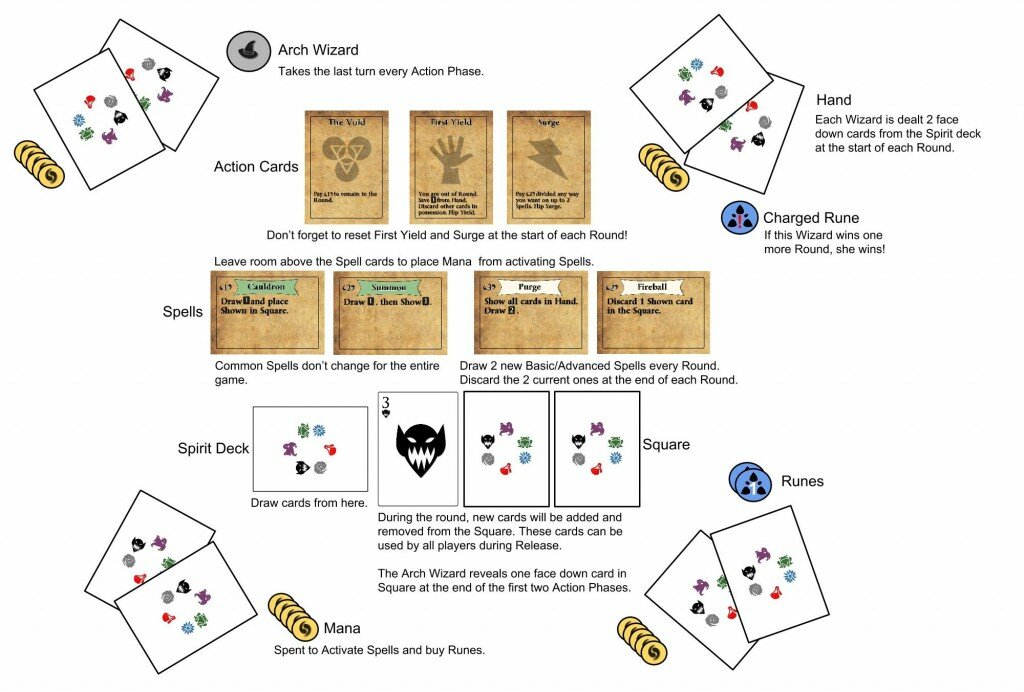

Because I was obtaining the icons and because my graphic skills are limited, the overall look and feel of the game is simple, clean, and modern. Here’s a card to demonstrate this point:

You can see one of every card on Facebook here. This style was shared throughout the game’s assets, including the game board, the rules booklet, the stickers, and the player boards.

All designers do some form of graphic design for their prototypes. This project has been very instructive to me both in how to do layouts and execute tricks in Photoshop. Experienced graphics folks will giggle at what I produced, but I did my best and I learned a great deal. I created dozens of iterations for the player boards, refined the rules dozens of times, and even experimented with the relatively simple board.

Never undervalue the importance of properly communicating elements to your players.

Art: The Goofs

I did two stupid things. One is something most publishers do, for better or worse, the other is just a goof of mine. Firstly, my game isn’t the most colorblind friendly. In testing I used colors that did not share a colorblindness spectrum, but for the final game I opted for color. The four player colors are yellow, blue (oops) and green, red (double oops). Were this a fully published game, I would probably do something more along the lines of green, yellow, black, and white. Maybe. I’m not sure and right now it’s not something I’ll change.

Fortunately, the cards and game boards are very color blind friendly in regards to the information presented. But, the game pieces are less so if you’re colorblind.

The second goof also has to do with color. I’ve always used red to indicate “offensive tactics” and blue to indicate “defensive tactics.” These items also have symbols, but the colors really drive it home. My prototype did not feature red. The final game does. Now, there are red and blue player colors AND I use these colors for offensive and defensive tactics. Doh! It’s not the end of the world, but it is lame and it’s something I’d address in a real version.

Art: The Potential

The game’s assets are ultimately not very consistent. I knew this going in, so this is less a learning for me and mostly something to do differently if this were a real publication effort. The key differences is that I would have added additional process and layers to it as well as hired a graphic designer.

I also would have hired the illustrator to craft more art. Instead of 5 cards with 4 colors each, I would have made the cards color agnostic and created a unique set of 5 cards for every faction. This would have quadrupled my costs, but also made the game more varied and exciting visually.

When creating the art, I hired the illustrator (John) and map artist (Robert) simultaneously. The cards have a very painterly style and the map looks like, well, a map. In a full printing, I would have hired the illustrator first. After he (or she) created a handful of assets, I would have then sought a map artist who could work within that style and remain consistent. Another option would be to have a graphic designer create a wireframe then simply have the artist do an aesthetic pass to make it look gorgeous and consistent.

I would have also hired a graphic designer to create icons, improve my layouts, and do an aesthetic pass on all UI. When I say improve my layouts, I say that because I would still create everything. I would mail the graphic designer a copy of the game with all my assets, have him (or her) learn to play it, then with his expertise, improve upon it. From there, he would make it beautiful. As the designer, I expect myself to know what my player’s need best. I expect the designer to know slightly more than me. Ish.

The mapmaker wouldn’t begin the map until he received an improved wireframe from the graphic designer. I sent the mapmaker a layout, but it wasn’t the final one. Granted, not much changed, but still, these things matter.

I would also retain the artist to do an aesthetic pass on the icons created/sourced by the graphic designer. If you look at what York actually has, it’s painterly and somewhat fuzzy illustrations (intentional) with clean, sharp icons. These would be merged and made consistent.

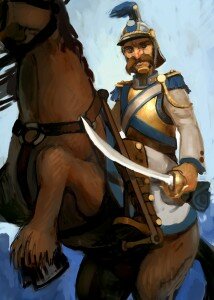

Stylistically, I would also direct my team to create something that fit the fiction better. Currently, the game is set in the 19th century with some decidedly 21st century styled lines. Clean clean clean. I’d like to see a parchment vibe, something that makes me think of the time period. Island Siege by Ape Games and graphic design by Daniel Solis did this well. Here is their player mat:

In my mind, these are fairly obvious decisions based largely on time and money. Could York look better? Sure! But, the cost to do so isn’t worth the money I will make for it. To summarize my notes here:

- Hire a graphic designer

- Leapfrog between artists in order to maintain consistency

- Create a more appropriate aesthetic to match the theme

Marketing: The Actual

I didn’t do a very good job marketing Battle for York. Much of this have to do with me thinking to myself, “it doesn’t matter much.” I like to develop my games openly and as a result folks may feel overwhelmed by the amount of information I share. At work, PR always guides us to have 2 or 3 points and stick to them. Market those 2-3 things precisely and repeatedly. With York, I posted about development (balance, UI, testing, mechanics, etc.) and shared everything as it became available. I should have shared things more sparingly.

If you notice with Blockade, I’m mostly teasing it via Twitter. I’ll write fewer posts and they’ll matter more. Of course, if you EVER want to know anything about my projects, email me. I’m an open book.

Another example is that when John was sending me assets one at a time, I simply shared them on Twitter. I believe there is a more effective and potent way to wield these beautiful surprises. In a proper campaign, I would have merged my Faction Previews with the art reveals. I also would have crafted a more elaborate fiction and story for each. There would have also been a video format. Just imagine how fun this would be!

The intent, would be to build hype and excitement for the theme and mechanics of York bolstered by gorgeous visuals and a well-crafted fiction.

I asked people, somewhat, for thumbs on BGG, but I don’t like spamming folks for what is ultimately an exercise in pageantry, and as a result I don’t have many thumbs. You have to ask for things!

Once I receive my copy of York, I’ll do a video unboxing to show the components and create a video tutorial to explain the game. I’ll also be sending a copy to a few reviewers. Finally, I’ll have it with me at GenCon to share and demo.

Marketing and Kickstarter: The Potential

I actually detailed some of the things I’d do differently above. So much for that format! The truth is, York is too big of a game for me to self-finance and I would have to run a Kickstarter campaign for it. Let’s discuss the Kickstarter I would have run. Before we get into Kickstarter…please don’t freak out. These are just my opinions. There is no right way. There is no single way. This is simply what I think would be my way based on my own experience with Farmageddon and a lot of observation.

Obviously, before the game launched, a handful of reviewers would have a nice prototype of the game in order to review and share. It blows my mind that some people still launch a game on Kickstarter without critical reviews to vouch for the game. This is a no no.

Before I launched on Kickstarter, all art assets would be final, all graphic design finished, and all rules final. I personally don’t like the “NOT FINAL” caveat. I’d self-finance this and say “boom, here’s the game. THIS is what you’ll receive.” It’s a personal choice and ultimately, everyone should do what they feel is best. This also helps you stick to your manufacturing schedule. Many KS projects still have to finish the game after KS.

I would share a PNP and also share a small number of copies with common BGG users to comment and discuss. This was very powerful for Farmageddon’s campaign and I feel sharing a PNP shows confidence. I would also take a note from Stonemaier Games and provide a money back guarantee. Now, before I did this, as mentioned at the very top, the game would be tested even more to fully relax me when giving this guarantee.

Stretch Goals are probably the thing I like least about the current Kickstarter ecosystem and it would definitely be a problem for me with York. I don’t like many of the extras for a few reasons:

- The extras packed in can really increase the MSRP, which can hurt long-term sales.

- I want to present and create the game as it’s meant to be. No more, no less.

- They make publishing, an already difficult thing, a bit more wild and unpredictable.

Nevertheless, here are the stretch goals I had in mind for a Battle for York campaign:

-

Additional factions: York features four asymmetric factions. Manufacturing more is really just a matter of a player board and 25 cards, plus the art. I would design and test 2 more before the campaign so that adding them wouldn’t be a big deal.

-

Stories: I hired a writer to create two short stories for the current game. In hindsight, these would be awesome stretch goals. Craft stories for every faction that go beyond the “short story” limit.

-

Promo Cards: I created some of these for the current version (Tactician, Saboteur) and really like how they change up and in some ways, break the game. I think good promos are fun and I’d probably do a few of them for a KS campaign.

-

Custom Tokens: The game would largely use punchboard tokens to keep the game at a lower MSRP. However, for scoring and turn order tokens, I could have neat custom meeples created. Note: The current game uses all wooden components, so in that sense, it’s arguably nicer than the “real” version. This is probably the least likely goal I’d pursue.

-

Bag: To cut down on MSRP I’d remove the bag from the base set. But, as a stretch goal for backers, I could include the bag. Note: There’s a bag with the current version.

-

New Maps: The current maps are balanced and designed for straightforward gameplay and symmetry. I’d love to create weirder maps that shift the gameplay, add new mechanics, and really vary things. Adding new maps is simply a matter of adding more boards. Oh, wait…those are super expensive! Still, something I could “add” much like Days of Wonder did with the Memoir ’44 Winter/Desert board.

All of these would be estimated and quoted before the launch of the campaign. If my goals were hit, I’d simply reveal the next stretch goals. They would fit within my budget and I would not lose money. As a side note, I really like how Mercury Games Kickstarted The Guns of Gettysburg. They had a very upfront, honest policy regarding Stretch Goals.

My funding goal would probably be around the $10k-20k mark. I know that’s a big gap. The minimum number of copies is typically 1000 and 1500 (depending on the manufacturer), but I’d prefer to print at least 2000 as that’s where you begin to see price breaks. Margins improve here, but your investment greatly increases.

Ultimately, the number I decided would be based on the amount of money I’d be willing to put towards it.This was one of the reasons I didn’t KS York — It’s more of a niche game and I’m not sure it’s the one to put $10,000+ of my savings towards. I hope to design and publish that game (or sign someone else who does), but I’m not sure York is it.

I prefer Kickstarter projects with a few, simple backer levels. Typically:

- Get the game for the US

- Get the game for Canada/Europe

- Get the game for somewhere else

Foreign backers would probably need to buy multiple copies to make it cost effective, but I haven’t gone deep enough into that to say for sure. My Kickstarter page would be simple with the following information:

- KS video would largely be a 2 minute pitch. “This is why you should back.”

- Page would detail components at a high level, link to reviews, share some of the art (cards, game board).

- Page would give a quick glimpse into the world’s fiction.

- Page would have a gameplay video. “This is how you play.”

The campaign would last for 30 or fewer days. I would be highly responsive and transparent for any questions ask (see the Farmageddon campaign for proof!). I sent several RFQs and settled on a manufacturer who would create a high quality game, was nice and reliable (from personal referrals), and could help me make the game at a $40 MSRP. I just didn’t pull the trigger.

Fulfillment and Post-KS Sales: The Potential

Fulfillment is a tricky subject. There are so many options and ways to do it. I know a few that I would NOT use. As for what I would use, I’m currently leaning towards doing it myself (if sales were low) or using Amazon fulfillment. Amazon could also help with shipping to European backers, again, if sales warranted such a thing.

In the short run I would rely heavily on Amazon’s storefront. Doing so gives me a place to store the games, a nice, safe, outstanding web store, and lets existing Amazon customers use their logins, their credit card info, and Prime status to get free shipping. Basically, I wouldn’t invest in my own Hyperbole Games storefront until sales warranted such a thing.

I would immediately begin the slow, challenging process of getting into the traditional distribution channels. There are a lot of great distributors and it would take time to build a great relationship with them. I would need to attend trade shows like GAMA and GenCon with some presence in order to do so. It is so key to be in FLGS to reach a mass audience. Once in an FLGS, my hope is that superior art and a very reasonable price would warrant a look from potential customers. Those two elements are so very key.

I would send the game to additional reviewers, especially ones with a large presence like The Dice Tower and some of the popular war game reviewers, like Marco Arnaudo. I would absolutely save some of these for after the KS campaign.

I would also begin creating expansions. I’m a huge proponent of the expansion driven business model. I love it as a consumer, a designer, and a publisher. As a consumer, it gives me more of a thing I love, but also, it’s my choice to do so. As a designer, I get to create content atop a foundation. Content is so much easier than mechanics! You also get to dream up and create less typical elements. With the base game, you want to cover your bases and hit as many people as possible. With an expansion? Go nuts. Finally, as a publisher you are able to drive additional revenue off the same IP. You can leverage existing art assets and branding. It’s also less risky to create a smaller expansion than yet another full game. Many of the most successful publishers utilize the stuffing out of this business model, including:

- Days of Wonder: Ticket to Ride, Memoir ’44, Smallworld

- Steve Jackson Games: Munchkin

- Plaid Hat Games: Summoner Wars and hopefully Mice and Mystics

- Mayfair: The Settles of Catan

- Fantasy Flight Games: Almost everything they make. Lately, Netrunner, X-Wing, and older titles like Arkham Horror.

Over time, the hope would be to build a small, core audience who continues to support the game’s expansions. In turn, I would support them with scenarios, PNP components, and the obvious rules support. Byron Collins of Collins Epic Wargames does a great job of supporting his community. So does Plaid Hat Games. I would like to emulate this. This core of consumers would hopefully grow via word of mouth and eventually I’d be a millionaire. Or, I’d simply reprint and improve the game.

Ha.

Conclusion

This post is absurdly long! I apologize. This post covered:

- Development: Actual versus Potential

- Art Development: Actual versus Potential

- Marketing: Actual

- Marketing and Kickstarter: Potential

- Post KS Sales: Very hypothetical potential

This post was fun for me to write and share, but most importantly, I want it to be useful and interesting for you. Were you looking for specific information not covered? Did I gloss over something? Please feel free to comment below. Or, email me your question at grant[at]hyperbolegames[dot]com.

Thanks for reading. I sent Battle for York to the printer last night and I am so very excited to hold it in my hands.

The best way to make sure your game always plays as expected is to test the extremes. If a player can roll all 1’s in your dice game and is guaranteed to come in last place, that doesn’t just indicate that one in a million games will be an auto-loss, it strongly suggests that many games could be skewed to the point of being unfun. If, on the other hand, there is no combination of luck that can guarantee a loss, perhaps given a particular strategy, then you can be confident that no game in the possible spectrum will be ruined for that reason.

The best way to make sure your game always plays as expected is to test the extremes. If a player can roll all 1’s in your dice game and is guaranteed to come in last place, that doesn’t just indicate that one in a million games will be an auto-loss, it strongly suggests that many games could be skewed to the point of being unfun. If, on the other hand, there is no combination of luck that can guarantee a loss, perhaps given a particular strategy, then you can be confident that no game in the possible spectrum will be ruined for that reason. It’s entirely natural to keep adding cool new things to your game. A is cool, therefore wouldn’t A+B and A+C be even cooler? Whether they are or not, you need to seriously consider whether those additions are needed to make the game fun or if they just add more bulk to the rules and thus length and difficulty to learning the game.

It’s entirely natural to keep adding cool new things to your game. A is cool, therefore wouldn’t A+B and A+C be even cooler? Whether they are or not, you need to seriously consider whether those additions are needed to make the game fun or if they just add more bulk to the rules and thus length and difficulty to learning the game. Sometimes a game knowingly includes a rule that’s impossible for other players to verify for correctness, and sometimes these tricky situations just sneak in. “Draw two cards, then put one back on the top of your deck.” If you put the cards you drew into your hand, your opponent can’t be sure that the card you put back was part of that pair or had already been in your hand. If you’re not paying attention, you may not even be able to tell.

Sometimes a game knowingly includes a rule that’s impossible for other players to verify for correctness, and sometimes these tricky situations just sneak in. “Draw two cards, then put one back on the top of your deck.” If you put the cards you drew into your hand, your opponent can’t be sure that the card you put back was part of that pair or had already been in your hand. If you’re not paying attention, you may not even be able to tell.