Post by: Grant Rodiek

I have three games deep in the furnace of development right now: Hocus Poker, Dawn Sector, and Sol Rising. Hocus is thankfully mostly finished — we’re balance testing now. Dawn Sector is with Portal Games, so they’re taking the lead on it. This has allowed me to focus my efforts on Sol Rising.

If you recall, I played Sol Rising with a publisher I’d very much like to work with at BGG. I was given a few pieces of feedback, which are the focus of my efforts:

- Incorporate the story more.

- Ease setup. Get players into the game more quickly. It’s not so much a matter of time, which is relatively quick (and far faster than, say, Memoir ’44), but more the avalanche of components and things to look at.

I’m at the tail end of implementing my changes, which were the result of a great deal of design work. I wasn’t just writing more narrative moments, though that happened as well. Before I discuss this work, in the hope it’s useful to you as a designer, I want to provide a brief recap to folks about what Sol Rising is.

Previously, on Sol Rising…

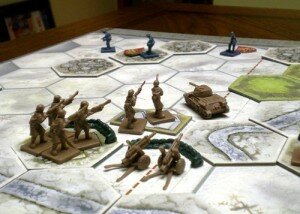

Sol Rising is a light to medium weight tactics game for two players. Well, there’s a team campaign in development and skirmishes (i.e. non-campaign) can be played with more than two, but it’s designed for two. Players take on the role of admirals in command of squadrons of capital ships, like battlecruisers, and fighter wings. The balance of force is similar to what you see in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi.

The game has about the complexity of games like Summoner Wars, Heroscape, or Memoir ’44 (if you add an expansion or so). The core mechanics of movement and combat are quite simple, but there are a few nifty features.

- Instead of controlling individual ships, you control squadrons of ships. An Ability activated by one ship affects the entire squadron. This gives you a bit of a “hydra” like effect for your forces.

- The board is a circle, which allows for a nice fluid map that feels like space.

- You need to use the right weapon for the job. Choose between guns or missiles depending on your target, and modify that further with abilities.

- The game features a 12 mission campaign with future scenarios affected by your previous actions and accomplishments. It isn’t a Legacy game, but it takes some of those elements.

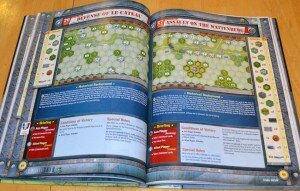

- 12 Unique scenarios, featuring different objectives, events, unique rules, and more. There’s a lot of variety here.

That last bullet is important. One of the reasons the game has taken so long to develop is that on top of a core game, I’ve had to essentially create 12 unique ways to enjoy that game. It’s been very challenging, detail oriented work.

It has always been my intent to make Sol Rising a very thematic game. There are the obvious elements: a campaign paired with a fleshed out narrative and universe, lots of ships with names and stories, characters. But, I’ve also tried to do this with intuitive and exciting actions, interesting events that help you tell stories, and difficult missions. In many scenario based games, the missions are fairly balanced. Often a 50/50, or close to that. Not in Sol Rising.

I was very inspired by the Battle of Hoth, in which the Rebel forces couldn’t really win, but they could have lost far worse. Really, if anything, the Battle of Hoth was a botched Imperial victory. Starcraft (on the PC) did this very well and it’s something I sought to emulate. Some missions are desperate and unfair, but thanks to the campaign structure, you can do your best and see what results.

That should give you the general idea, and if it doesn’t, ask below.

Better Incorporating the Story

At BGG, my prototype primarily exhibited story via the campaign book. Before each mission, and sometimes at the end, you’d read a little story that would introduce the scene and set the stage for you to play it out. I was encouraged to introduce the characters into the game and infuse some mid-scenario story moments.

Let’s begin with characters. My story has always had a diverse cast of characters. However, they’ve never been IN the missions. My first concern with adding characters was figuring out where they’d come in. To give myself enough flexibility, I decided to assign them in three ways.

- Fleet Commanders: Big powerful characters than can affect any ship in your Fleet.

- Squadron Commanders: Assigned to a single Capital Ship squadron (1-3 ships). They can only affect that Squadron.

- Wing Commander: Assigned to your 1-4 Fighter Wings. They can affect any of your Fighters.

So, for example, at the start of the mission you are told you have Commander Eric Schmidt. Choose one of your capital ship Squadrons and place his card next to it.

My next fear was adding another layer to consider. On their turn, a player chooses one squadron (capital or fighter) to activate. With that squadron, they can move, attack, and activate abilities. The abilities are what make that complex, as you can have a few in play at a time to consider. I was worried about forcing players to make choices with their Commanders as well.

The solution was borrowed from my Events. Events are triggered randomly as a result of Combat. When an Event is triggered, you draw 1 face down token from a pool of 10. The tokens share 1 of 4 generic symbols. Every mission, these symbols mean something different and have an affect that is appropriate for that mission. What Event comes out, and when, can really change the game. It adds some nice spice and variability to the battle.

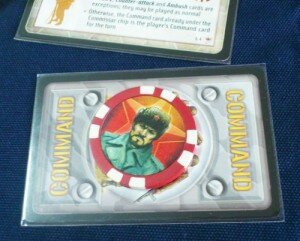

I wanted Commanders to matter, but I didn’t want you to greatly alter your command decisions because of them. Therefore, I gave every Commander 1 of the 4 Event symbols. When that symbol is drawn, you immediately use the Commander’s ability. It’s an unexpected bonus.

You can see an example above. Whenever the Star Event is triggered, the Squadron to which Commander Schmidt is assigned immediately moves up to 3 spaces. It’s simple, quick, and will have an impact on the battle.

On the back of every card is a bio of the character. This gives you insight into who they are and how they think. Now, when you read the introductions to every mission, you’ll also be given insight into which characters will augment your fleet.

Next, I needed to introduce more story moments into the game. How would these trigger? Why? And when? I realized relatively quickly that I already had an outstanding vessel for these: Objectives. Every mission has 1-4 objectives, most of which are optional. These objectives are tied to entities in the world. For example, in the very first mission, the Martians have an objective to escort a Merchant ship to the jump point to warn the others.

When I began thinking about adding narrative moments to these objectives, I realized this would solve one of my other problems. Previously, players had to reference the campaign book to look up objectives or remember what to do. They also didn’t know WHY the objectives mattered until the following mission. It removed some of the punch of completing something. I killed two birds with one stone with the following solutions.

- Every objective now has its own double sided card. You place these next to the board, or in front of the player to whom the objective is assigned. Easy reminder.

- Every objective card has a little story on the front to set the stage and better incorporate why the objective matters.

- Every objective card has setup instructions if need be. For example, now, you just look at the card to add the Merchant. It removes it from the booklet, which makes the booklet shorter.

- Every objective tells you the trigger – when to flip it over.

- The back side of every objective has another story piece, which drives home, in the fiction, why your actions matter. It provides feedback within the fiction.

- Finally, the back side tells you why what you did mattered with clear language on the effect.

Above, you can see an example Objective card – the front side at least. Previously those bottom elements were parts of a very long list of items for setup. Now, those items are distributed, which already feels better. Part of what I’m battling here is perception, and this counters it.

So, we have characters incorporated into the Missions themselves, adding a new tactical choice/option and story moment. We also have the Objectives more seamlessly taught and paired with story moments for players to enjoy in the mission.

What else can we do to make the game feel simpler for setup?

Easing the Setup

One of the first things I sought to eliminate were environment tokens. Part of the game’s appeal is the variety of encounters. You have asteroids, debris, turrets, and more. Problem is, some of these can weigh down the setup time. I realized that I have several missions that feature asteroids, including the first one. My first solution was to make double sided board pieces: one blank, and one with asteroids pre-printed. On the first mission now, you simply use the asteroid side of the board. This goes for many other missions! This saves 5 or so tokens you need to place precisely.

Thinking about how much I liked the Objectives as cards and out of the book, I created a small little card to show all of the Events. That’s one less thing to look up in the campaign book and again, it shortens that already lengthy book.

One of the biggest problems was the number of squadron tokens. Due to my mechanics, every squadron had 2 tokens, one for each formation type. This meant in a typical scenario you were gathering and organizing around 20 different tokens. Yech! I came up with a solution that more or less preserves the intent of my formation mechanic, while greatly simplifying it. This means fewer rules and cuts the tokens in half.

Previously, you’d arrange your ships in formations, like a triangle (one in the front, two in the fear) or spear (three in a vertical line). The formation would dictate who could be attacked. If a ship is attacking a spear from the front, the rear two ships couldn’t be affected. It was an okay idea. It wasn’t quite pulling its weight, though. Now, there are no formations. However, if even one ship in a Squadron has shields, it must be targeted before Ships whose shields are down. That is, unless you attack the ships at point blank range with guns, or use bombers to get inside a squadron’s formation.

That’s all good, but my pile of tokens served two purposes. One, as mentioned above, to denote the current formation on the board. The second, was that the unused token would be placed by the formation to help you remember which squadron was which. So, if Squadron B was in Spear, the Spear token would be on the board, and the B triangle token would be next to squadron B.

The solution here didn’t take long to discover. I put the responsibility onto the player reference board. There are slots on the side of the board for you to place your ships. This cleans up the play space and eliminates a ton of tokens. Notice I also added a slot for any Fleet Commander cards.

I implemented one more solution, which is something I’ve been putting off for a very long time: splitting ships into Martian and Terran fleets. Previously, there was a large pool of ships shared by both sides. Missions would denote which ships to use for each side. Players would find them in the deck and pull them out.

This was problematic for a few reasons. One, it’s fictionally odd. Two, looking through a deck of 60+ cards is far worse than looking through a deck of 30 cards each. Thirdly, it misses an opportunity to make the fleets slightly unique. I’m not sure if they need to be Summoner Wars unique, but I think making both players draw from identical pools isn’t ideal.

As I began thinking about the fleet assignments, I realized I could arrange these cards to help me even more. The game is divided into 4 arcs:

- Missions 1-3, the introduction

- Missions 4-6, focusing on Martian characters

- Missions 7-9, focusing on Terran characters

- Missions 10-12, conclusion

I’m going to divide and sequester the ships according to their arc. When a player opens their box, they’ll see a small packet, baggy, or box that says “Missions 1-3.” They can ignore they rest. This means they’ll be looking at 30 or so ships total. Those will now be divided between the two Fleets. This means players have fewer cards to sort through and it’ll take less time to find them.

It also means that by Mission 3, players will be very familiar with their ships, comfortable, and ready to learn something new.

To accommodate this change, which requires a bit of administrative work to make sure everything is organized between my campaign book and the new fleets, I created my Sol Rising Shipopedia using Google Spreadsheets. This document lists every ship, its stats, its fleet, the missions in which it appears, and its ability. I also took this time to take yet another pass on tuning, changing, and improving the abilities. They’re getting tighter and more balanced every day.

The Summary

Let me condense all the changes for you here.

- Commander cards can be assigned to your Units to provide bonus actions when certain Events are triggered.

- Objectives are now represented on cards, which provide mid-mission story moments and dialog and feedback on what you accomplished.

- There’s an Event card to help you reference Event effects without opening the campaign book.

- The board now has an asteroid and plain side to ease setup.

- Formations were replaced with a shield mechanic.

- Squadron tokens were cut in half. Ships are now tracked by placing them adjacent to the redesigned reference board.

- Ships are now assigned to either the Martian or Terran Fleets.

- Reviewed every ability, throwing many away, designing new ones, polishing old ones, and ensuring consistency between all of them for style and text.

- Ships will be packaged and presented based on arc.

Advice for Others

A few things really stand out to me as potentially useful for other designers who are looking to incorporate story better into their games, or simply revise a mature design to match any feedback.

Take advantage of your existing systems and features. With Commanders, I didn’t design a new mechanic players need to concern themselves with. You reference a symbol and take a bonus action when events occur. That’s simple and easy to learn. Some games won’t have much to lean on. A simple game like Hocus Poker doesn’t have much for us to leverage for new features. Thankfully, we don’t need any. But, Sol Rising is a meaty game with many features and elements. I could have added something new, sure, but I took advantage of a feature that’s not only one of my favorites, but one of my testers’ favorites.

It should be obvious, as table top design is for a physical medium, but remember to consider components as a solution to your problems. Many of my issues were solved by introducing new cards, reference boards, or other items to help stretch out the information and communicate the story. Now, cost is often a very decisive factor, but thankfully for me it wasn’t. I’ll stress that even if cost IS a factor, you should allow yourself some open creative space to see what’s possible. Don’t shut that door before you’ve really thought through your options. Remember to consider components as a potential solution.

Always remember that once your game has reached the complexity level you desire, if you add something, you need to remove something. I added Commanders, so I removed formations. Formations previously were an action a player could take on their turn, that required players to understand double the components that now exist, and the rules for it. Now, it’s just a single rule (shields). I think my complexity is actually lower now, so it was a net reduction, which I think is good! Another way I simplified the game is that I made it such that several ships share abilities now. I also removed abilities that were too complicated. When iterating on a design, consider your desired complexity level and what it’ll take to remain there.

Games are an interactive medium. Something designers constantly forget when designing story for games is that the story should be about the players’ actions and choices. I hate when a video game removes control from the player and forces them to watch a character talk. Games aren’t books and they aren’t movies. They are interactive! That’s why I’m proud of how the objectives tell the story. Yes, the introduction isn’t interactive. It’s setting the stage. But after you destroy the space station and you get to read the dialog on the back, it’s the result of something you did. It’s based on your choices. If you don’t blow up that station? You won’t see that dialog. I think that’s powerful. This will especially pay off when you see how the persistent effects continue to evolve the game.

I hoe this was interesting and insightful for you. Please share your thoughts and ideas in the comments below. Thanks for reading!