I bumped into Chevee Dodd on Twitter. A few weeks ago, he approached me about writing about his upcoming game, Scallywags, on this site. I was a tinge apprehensive at first, as I didn’t know him that well and I don’t want Hyperbole Games to just be another PR platform. I inquired about his game and all apprehension immediately ran out the door.

Chevee’s game Scallywags was recently picked up by the outstanding publisher Gamewright. This is a huge accomplishment for any designer and it’s one I’d love to share at one point. Chevee asked me what to write and I told him to tell a story. One of my goals for Hyperbole is to showcase great work from other designers — this is great work. Grab a cup of coffee to read Part 1 of Chevee’s story. Part 2 will be posted on Friday.

Guest Post by: Chevee Dodd

Never give up. Rejection Is Part of the Process

In 1997 I found myself adrift in the gaming industry. Like many gamers at that time, I discovered our hobby through Magic the Gathering. I loved collectible card games, but I had not yet been introduced to eurogames. Strictly through chance, I found myself in a position to travel with United States Playing Cards during the summer to demo the X-Files CCG at their convention booths. Along the way, I discovered the German phenomena that was Settlers of Catan (which was not yet printed in English) as well as some excellent American games that were fighting for this new sector of the market.

I met James Earnest at Origins that year. He had a single tiny table next to our booth and struggled to sell his games for most of the show. Saturday, in open gaming, he showed up with a briefcase full of games and started demoing. By noon on Sunday he had sold out of his product and was taking pre-orders for the next batch. Jame’s games were quick, simple, and fun. They didn’t offer a great deal of difficult decisions, but they kept players coming back for more. I was inspired. “I can design these games,” I told myself.

I vowed to make a game as I left Origins. I took a box of my boss’ business cards and told him that I was going to design a game and draw the cards on the backs. He laughed, but I was dead serious. It took a week or so for me to find inspiration, but like so many of my ideas, it hit me quickly. I had also discovered Lunch Money during Origins and I absolutely fell in love with its simplicity and interesting play decisions. The problem at that time was that I primarily played two player games. I had found a goal: Make a game similar to Lunch Money, but for two players. In a flurry of inspiration I completed the design in about a half hour. When I say completed, I mean done. The game has never changed from that first concept. I spent an hour or so drawing each card. My friends and I still play it and laugh at the silliness of it today.

I know this anecdote has nothing to do with Scallywags directly, but I tell this story to make a point: this was the beginning of a very long journey for me. A journey full of disappointments and rejections that eventually led to Scallywags.

I had designed a game and I thought it was good enough for publication. So did my friends. We had played it hundreds of times after all! It had to be good! The problem with the game was that it was one big inside joke. The cards and flavor were all based on that summer convention season that only included myself, a close personal friend, and a bunch of guys from a company 400 miles away. That’s no problem, though. Right? Any Knizia fan can tell you that slapping a theme on a game is easy! And that is exactly what I did. I slapped a few themes on the game and sent out some letters of introduction to various publishers.

Within a few weeks I received interest from a few publishers. They asked to see my rules for the game. Excitement was high! I could write a pitch that interested people and surely that meant I could make games that they wanted to publish. After some more waiting, I received requests for prototypes. This was the big time, I was sure of it. All I had to do was send off some prototypes and wait for the contracts to roll in. That never happened. I merely received some nice, informative rejection letters. In some cases, I even received my prototypes back in the mail. That’s a disheartening moment. It’s like someone mailing back your discarded dream.

Luckily, I was still young. Rejection just hardened my resolve to try harder. I didn’t stop designing games and I didn’t stop trying to get published. I learned a great deal from those first efforts. I learned to be more selective in my choice of publisher. I learned to refine my prototypes and make them as functional and presentable as possible. Most of all, though, I learned to accept rejection. It is a part of the process.

Everyone in every creative position faces rejection. Authors, musicians, programmers, inventors, artists, photographers… the list goes on. This process is no different for game designers. Learning to let go of the emotional attachment you have with your work is a very hard lesson to learn.

It proved to be a lesson that I would have a difficult time accepting. I was so jaded by rejections that I stopped trying to find a publisher in the traditional manner. I decided to explore a new territory, Print and Play.

Print and Play

The original inspiration for Scallywags came in 2008 during a family trip to the beach. During that trip I read Treasure Island for the first time. I was in a pirate mood and wanted to design something using coins. Further inspiration came one evening while browsing BoardGameGeek.com. I found a BGG user named Jeremiah Lee who had designed a neat little game called Zombie In My Pocket and posted it on BGG for everyone to consume. For free. I hadn’t encountered Print and Play before that point, but I was instantly awed by his success. His game received significant traffic and it wasn’t long before other people started making custom sets with fancy graphics. It was the ticket I had been looking for. A way to share my games with the world without fighting through the publication process.

The actual design process for Scallywags was not all that dissimilar to my first game design from 10 years prior. There was a flurry of inspiration, some quick math, and I immediately started working on the first prototype. The game involves coins that only have their value printed on one side. While that is not necessarily a unique component, I had an interesting mechanic to go with it. What if the coins were shaken up and dumped on the table to land either face up or face down?

I thought that would be a neat way to randomize point distribution so that not all information was perfectly available. I had already decided that players were trying to amass the most gold, now I just needed to figure out a way to distribute the coins to the players. That’s where cards come in. Going back to some of the fun take-that mechanics of James Earnest’s Cheapass Games, I wanted to have players taking coins and giving coins from this central pile. Players would be able to look at face down coins and hand them to opponents, or take the risk and snatch up face down coins for themselves without looking first. There’d be cards that would let you steal opponent’s coins and cards that let you trade.

A little bit of math helped me work out how many coins there would be of each value as well as how many of each of the eight different cards would appear in the deck. This is the part of designing that I really love. I’m not a mathematician or statistician. I’m not even really all that smart. However, I love breaking games down and analyzing the related probabilities. It is exceptionally rewarding when it is my own game. I only spent about an hour working through the specifics of the coins and cards. I was already in love with the game and wasted no time starting on the artwork.

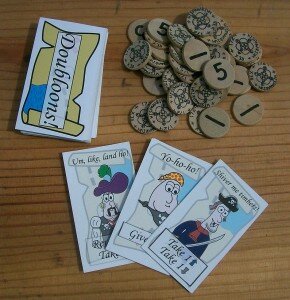

Now, I can draw some cartoon characters, but I’m no artist. The good news is that this was a goofy game and my little characters were a perfect fit. I was so sure that this game was going to be good I didn’t even playtest it before the art was done. The first time I presented the game to my regular group, I had a full color printing of the cards and slick wooden coins that I stamped with a custom rubber stamp. In fact, the components never changed from that fist playtest through submitting to BGG and the publisher. Sure, some rules changed, but the components worked well together and my math turned out to be pretty solid.

The game was titled Doubloons! at this time. I had wanted to call it Loot, but I learned that there was already a game titled Loot that just happened to be about pirates and their treasure. I picked a new name and submitted it to BoardGameGeek. I remember waiting for it to be approved. It took days, but felt like weeks.

Meanwhile, I refined the files a bit and tidied things up for printing. I used business cards for prototyping because they are generally the same size and shuffle easily. With the advent of printable business cards, I didn’t see any reason to do anything differently. The card files were formatted to be printed on punchable business cards and I reduced the rules to a single page.

I was ready for BGG fame. I was certain that I had picked a theme and a specific set of mechanics that would appeal to a broad range of BGGers and soon I would be swamped with fan mail. That almost happened!

Thank you for reading Part 1 of Chevee Dodd’s story! Come back Friday to read Part 2.

The best way to make sure your game always plays as expected is to test the extremes. If a player can roll all 1’s in your dice game and is guaranteed to come in last place, that doesn’t just indicate that one in a million games will be an auto-loss, it strongly suggests that many games could be skewed to the point of being unfun. If, on the other hand, there is no combination of luck that can guarantee a loss, perhaps given a particular strategy, then you can be confident that no game in the possible spectrum will be ruined for that reason.

The best way to make sure your game always plays as expected is to test the extremes. If a player can roll all 1’s in your dice game and is guaranteed to come in last place, that doesn’t just indicate that one in a million games will be an auto-loss, it strongly suggests that many games could be skewed to the point of being unfun. If, on the other hand, there is no combination of luck that can guarantee a loss, perhaps given a particular strategy, then you can be confident that no game in the possible spectrum will be ruined for that reason. It’s entirely natural to keep adding cool new things to your game. A is cool, therefore wouldn’t A+B and A+C be even cooler? Whether they are or not, you need to seriously consider whether those additions are needed to make the game fun or if they just add more bulk to the rules and thus length and difficulty to learning the game.

It’s entirely natural to keep adding cool new things to your game. A is cool, therefore wouldn’t A+B and A+C be even cooler? Whether they are or not, you need to seriously consider whether those additions are needed to make the game fun or if they just add more bulk to the rules and thus length and difficulty to learning the game. Sometimes a game knowingly includes a rule that’s impossible for other players to verify for correctness, and sometimes these tricky situations just sneak in. “Draw two cards, then put one back on the top of your deck.” If you put the cards you drew into your hand, your opponent can’t be sure that the card you put back was part of that pair or had already been in your hand. If you’re not paying attention, you may not even be able to tell.

Sometimes a game knowingly includes a rule that’s impossible for other players to verify for correctness, and sometimes these tricky situations just sneak in. “Draw two cards, then put one back on the top of your deck.” If you put the cards you drew into your hand, your opponent can’t be sure that the card you put back was part of that pair or had already been in your hand. If you’re not paying attention, you may not even be able to tell.