This is Part 2 of Chevee Dodd’s story about designing Scallywags and finding a publisher. Here’s Part 1.

Guest Column by: Chevee Dodd

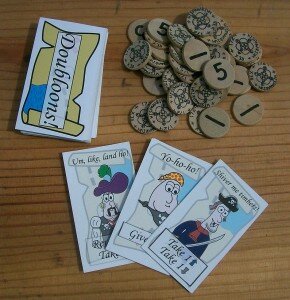

Shortly after submitting Doubloons! to BoardGameGeek it received a bit of attention. A few people even made sets and tried it out! Some people left comments. Some people posted in the forums. Some people sent me messages. Some people even started working on their own versions with updated art and layout! The few people that tried the game were very encouraging. They told me that I had something and that I needed to give publication another shot. I had already begun working on my next game and had abandoned traditional publishing for this new found freedom. It was liberating to be able to share and discuss my game with complete strangers.

The fans persisted however and I gave in. I made a deal with myself. I would pick one publisher and I would send them an introduction letter. If they picked up the game for publication, great. If they didn’t, I would continue to work Doubloons! and other print and play games and never look back. Obviously, the fans were right, but the journey to publication was not a simple ordeal. Not at all.

I spent a bit of time researching publishers. I had a few in mind and I wanted to pick the one that really made the best sense for both parties. With a bit of study and deliberation I picked Gamewright. I needed a publisher that worked well with light family games. I needed a publisher that liked adding toy value to their games. I wanted a publisher that would put a great deal of effort into making sure the game looked great, played well, and appealed to everyone. Gamewright makes great family-friendly games with excellent components and stunning art. I knew they could give Doubloons! the treatment it needed. It just so happens, they are also the same publisher that produces Loot.

After I had the publisher selected, I started the process as I always had. I could not find submission guidelines on their website, so I resorted to a traditional introduction letter.

This is the email I sent:

I would like to submit, for your review, a game of my design. If I have not contacted you through the correct channels, I would appreciate the opportunity to present my game to the proper personnel. Thanks!

——————–

Title: Doubloons!

- Age Range: 8+

- Time to learn: 5 min

- Time to play: 15 min

Components:

- 50 cards

- 40 coins (in various denominations)

- 1 rules sheet

Description/Theme: Doubloons! is a light-hearted game in which players take on the role of swashbuckling pirates divvying up their booty. To begin the game the coins are dumped in a pile in the center of the table. The coins are only marked on one side and are left as they fall (face up or face down.) On their turn, players use cards to take doubloons for themselves or give them to their opponents. The coin’s orientation never changes. There are cards for distributing face-up and cards for distributing face-down coins; thus, throughout the game you will be giving players face-down coins and can somewhat manage an idea of what the value of their take is.

Play continues until all players have 10 coins, at which point the game ends and players total the value of all their coins. Biggest take wins!

I thank you for your consideration.

Chevee Dodd

The introduction was short and simple. The goal of an introduction letter is to quickly introduce the game, the required components, and the core concepts without going into too much detail. I did not attach the rules, nor did I include any images of components. The goal is to not waste the publishers time if they are not interested. Most publishers have a production schedule that may be years in advance. They may already have games in the production lineup that conflict with what you are working on. The theme might not fit their style. The game mechanics might not fit their brand identity. If they want to see more from your game, they will ask. If they don’t, they will politely tell you that they are not interested.

My reply came seven months later. The publisher was interested and wanted to see more. They asked for rules and any pictures I could provide of the components. I was told that it could take another 4 to 8 weeks for review after this information was submitted. This time it only took a couple of weeks and the publisher asked for my prototype! The only problem was that I had given my only prototype away during the Print and Play Secret Santa that ran on BGG that year! I scrambled to get something presentable together and mailed it off as soon as I could. I had made it this far a few times before and I was not getting my hopes up, but I did not want to damage my chances by being less than punctual. This process, after all, was what jaded me towards traditional publication in the first place and I wanted to be sure that I did everything I could to help the game succeed.

It was another five months before I heard back from the publisher. It was now September of 2009 and it had been nearly a year since I contacted them and over a year since I had designed the game. The testing was very positive and they liked the game! Unfortunately, they couldn’t commit to it yet because of a backlog in production schedules, but I was assured they could make a decision in early 2010.

Contracts and Lawyers

Well, 2010 came and went and nothing. We traded pleasantries a few times and I was assured that they were still considering the game. In the mean time, I had changed careers and started college. Game design had taken a back seat in my life. I stopped working on new games and had little hope for the future of Doubloons! I wanted to design games still, I had just been put on hold while other things needed my attention. It was not an enjoyable time in my life, but I got through it. Occasionally something new would pop up on BGG. People were still discovering Doubloons! and creating content. International Talk Like a Pirate Day was a popular time for the game. With card names like “Arrrrrrr” and “Shiver Me Timbers” it was a natural fit. That kept me hopeful that I could return to design and keep publishing print and play titles at some point in the future.

I learned something about print and play games in those two years. The more difficult the game is to create, the less chance people will put in the effort to make their own sets. Making forty coins with identical backs and different fronts is a difficult task. Not everyone wants to purchase a custom rubber stamp to imprint coins for a game they have never played.

September 2011, three years after I initially contacted Gamewright, I received an email. It had been almost an entire year since my last contact with them and my patience had paid off. They wanted to license the game! I received a preliminary offer that was quite generous with one exception. They wanted me to take down all print and play files I had put on the Internet. I was conflicted about that point. I had abandoned traditional publishing so that I could make my games available to everyone. I embraced a new ideal that I felt strongly about. I used open source software to design a game and I wanted to give it away. I realized, however, that the game was difficult to make. The coins made it prohibitive and I believed in the game. I wanted people to be able to play it. Being published by Gamewright meant that anyone could pick it up and play.

I accepted their initial offer and we started working on contract negotiations. I won’t go into specific details about the contract, but I will say that their offer was in my favor. I had read many horror stories about crooked publishing companies giving designers horrible deals that robbed them of their creation, but this was none of that. I am no lawyer, but from what I read initially, it sounded very much in my favor. I trusted the publisher in every way, but I did not immediately accept. First, I sought out the help of a friend that just happens to specialize in contract law. He gave everything a read and assured me that it was on the up and up. I encourage everyone in a similar situation to do the same. I was lucky to have a close personal friend available, but if not, I would have paid a different lawyer to review the contract.

I did ask for a few minor changes. The initial contract was very blunt in removing me from any and all discussions involving changing the game. I was perfectly comfortable with them changing anything they like, but I did ask to be informed. I did not want to receive the game at publication and be completely shocked at the changes. I did not want to have to answer questions about the product without being completely aware of every aspect. They obliged my request as long as they were given final say on everything. Not a problem.

My second request was that in addition to my allotment of free copies I be given one additional copy of each subsequent printing including any foreign language editions, or sub-contracted versions. This was a bit of a selfish request because honestly, I would love to have my game translated into multiple languages and I would totally love to have that on a shelf somewhere. It was also so that I could track print differences between editions. I wanted to be able to field questions about product quality if I were asked and I needed to ensure that I had an future printings to reference.

My game was going to be produced. A real artist was going to draw beautiful images and a skilled development team was going to tweak things until it was perfect. I was going to be able to hold the box in my hand and see my name on the packaging. It was no longer a dream.

Accepting Change

It has been over ten years since I received my first rejection letter. It has been nearly four years since I designed Doubloons! I spent more than two of those years waiting to be rejected by Gamewright. In the end, all of that patience has paid off. My game is going to be on shelves soon, but this past ten months have taken a whole new level of patience. Waiting for rejection takes apathy. Waiting for news about the treatment your product is receiving is maddening.

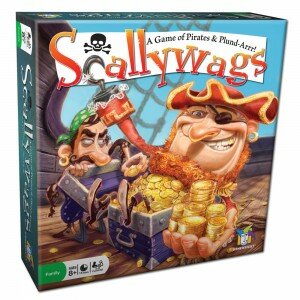

As soon as the contract was back in the publisher’s hands they approached me about changing the name. I was never particularly attached to the name Doubloons! so I did not have a problem with changing it. We collaborated on the effort and the publisher eventually picked the one they liked the most: Scallywags. The question I have been asked most about the publication process is allowing the publisher to make changes. I feel it is important for the publisher to have full control over the final product. They are, after all, in the business of selling games. As a designer, I design games that I enjoy. That does not mean, however, that my games are perfect and ready for the market. Game publishers employ developers that can take a raw design and polish it. Gamewright happens to have some great developers!

When it came to every change that was made to Scallywags, including the name, I took this stance: I am a game designer. I design games. The publisher sells games. They know the market better than I ever will. If they feel that a change will help the game sell, I have full faith in their decision.

This advice is particularly true with Gamewright, but I cannot promise you that all publishers have development teams that are as competent. You may have to apply this advice with a bit of apprehension in your particular situation. Whether you decide to accept change or struggle against it, be polite. You do not want to build a reputation as a designer that is difficult to work with. You may have a great track record of quality games, but if you are a pain to deal with, future publishers may pass on your submissions and accept games from less difficult designers.

Over the next few months various things changed about Scallywags. Some of the changes were made without my input, some we collaborated on. When I submitted the game I included a sheet of alternate/variant rules that had been tried during further playtesting. I wanted the publisher to know that I was comfortable with change. I cannot say that this addition helped them pick my game, but I’m almost certain it did not hurt. Many of the changes we made came directly from this sheet. I had always been dissatisfied with the end game, for instance, and we ended up going with a change that I wanted to implement should I have ever released a second version of the print and play. In fact, the game as it is published is very close to what I wanted the second version of the game to be.

Sometime in December 2011 I received a preview of the best change ever: the art. The publisher sent me a few card previews and I was floored. Until this point I had no idea that the publisher was using the same artist that worked on Loot. To say I was astonished is an understatement. The art is spectacular. The next bit of news that I would learn is that they were actually molding custom plastic coins for the game! I had expected punch-out cardboard, but Gamewright has gone the distance. I had secretly dreamed that they would. One of the reasons I picked them was for the great value they added to their games and that turned out to be a valid choice. The problem with that decision is that it has delayed production even longer. The game was supposed to be released in the first quarter of 2012, but instead has been pushed back because of the coin molds. That’s okay though. I would much rather wait for awesome bits.

So, here we are. On the verge of release. The game has been waiting for almost four years to be enjoyed by the public. I have dreamed of reading stories about families enjoying my games and it seems so close. There have been many trials and tribulations over the past decade. Many times I wanted to throw in the towel and walk away. I chose, however, to persevere. I have struggled to succeed and I am extremely close.

One thing this success has done for me is renew my faith in myself. I want to explore beyond print and play or professional publication. I have returned to my roots. I have a new found inspiration in open source software design. The idea that something can be developed with complete transparency and that anyone who is interested in the product can follow its creation from the beginning amazes me. I have set up a website where I could start designing games completely openly. I blog about every aspect of my design process. I have published each version of my prototypes and rules for everyone to try. I write articles about my design decisions and openly admit to my mistakes. It is not easy to share my creative mistakes, but it has been rewarding.

I can’t guarantee that any of my future projects will be published in a traditional manner, but I can promise that they will be made available as print and play. I design games for my enjoyment. Though I would love to continue having publishing success, I cannot allow that desire to hamper my creative process. I don’t want to design games for money… but if my creative process develops something publishable, you can be certain I won’t say no!