Post by: Grant Rodiek

I recently acquired Legends of Andor and after four plays it’s really making me happy. The game is scenario driven and does some very intelligent things to add replay value, but also present a specific story in each scenario. It’s a great mix of focus and unpredictability. In many ways, it’s similar to Robinson Crusoe. I broadened my thinking and began pondering the scenario design of Memoir ’44 and Combat Commander: Europe. Finally, I’m considering Mice and Mystics.

I sense a blog post.

Each of these games holds a high place in my heart, but also do things slightly, or dramatically differently to accomplish their goals. On the recommendation of Todd Edwards, and the seconding of Josh Buergel, I’m going to write about the various tools used by these designers in each game to present unique, dynamic scenarios. Three of these games are cooperative, two of them are competitive. They also scale nicely in terms of complexity.

We’ll begin with Memoir ’44, as it’s the simplest, and progress upwards in terms of complexity.

Memoir ’44: I gotta get a Luger for my kid brother

Memoir ’44 is a 2 player (more, with an expansion) tactical war game during World War II. Players command infantry, special forces, tanks, artillery, aircraft, and a slew of special weaponry (ex: machine guns, mortars) to win the battle.

How to Win: Point Driven. Points are earned by eliminating enemy Units and holding key positions.

Setup: No variation between plays. Units of a defined type and quantity are placed in specified places on the map. Terrain (forests, hedgerows, bridges, towns, etc.) are also placed in specified locations. Mission 1 is always the same at the start.

The slight exception is that in the campaign mode, your performance in previous missions can affect which reinforcements you bring to subsequent missions.

Variance: Variance comes about in a few ways. For one, the Allied and Axis force allotments and positions are different and not always equal. Players may have differing objectives. For example, the Allies may gain a Point for taking a specified point, whereas the Axis gains no point for doing so.

The game actually recommends, especially in competitive play, that players play twice, switching sides after the first game, and tallying their combined scores. As an example, I may play the Germans better than you, but tie you on the Allies, for a net positive performance.

Once the game begins, variance comes about primarily through player actions and combat resolution. For the former, players are both given a large hand of cards, often 5-7, drawn from a shared deck. Although there are a few very powerful cards that let a player move every Unit, or counter-attack, most are simple variations on a simple premise: move X Units in the defined sectors.

If you haven’t played Memoir, the game is divided into 3 sectors. Cards tell you how many Units in what sector can be activated. When activated, Units can Move, then Attack. For example, a card may say: you may active 2 Units on the left sector.

Though a player may get lucky on occasion with incredibly good draws, by and large, and over the course of many games, the draws are relatively equal between players. The skill comes from timing and knowing what card to use, on what Units, and when.

The final form of variance is through combat resolution. The attacker rolls dice to see if they can get a hit. The probabilities are identical for Units of the same type. Therefore, an Axis Infantry will have the same chance of shooting an Allied Infantry Unit, and vice versa. There are some variations in special units, but the rules are deliberately clean to avoid too many exceptions.

Naturally, probability being the beast it is, one player may have very favorable dice for the duration of a single game, but over the course of ten games, they should even out.

Conclusion: The game uses relatively standard variance mechanics via card draws and dice resolution to add spice to historically driven scenario setups. Playing a scenario multiple times, without adding in your own variables, or introducing expansions like Breakthrough or the Airpack, won’t be as compelling as playing a new one.

I believe Days of Wonder and Richard Borg know this as they’ve produced an astonishing amount of content. I own 98% of it and I’m telling you now, I can play Memoir until I die.

Legends of Andor: Let’s save the kingdom through story

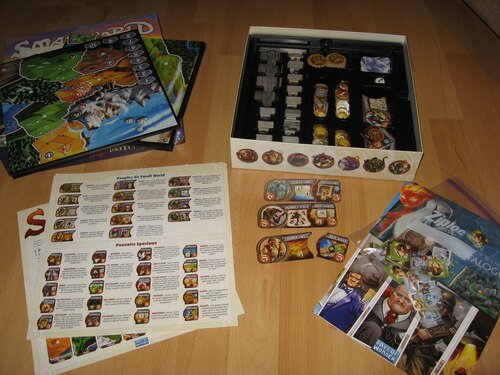

Legends of Andor is a 2-4 player fantasy cooperative game set in the fictional kingdom of Andor. The game features 5 unique scenarios, the first of which actually teaches you the game as you play. It’s very novel, but not the topic of this post.

Side Note: Legends of Andor has quite a bit of expansion content, including a large expansion releasing this Essen. Unfortunately, save for the base game, none of it has been translated and brought over. Quite a shame! There’s a free, official 6th scenario on BGG if you’re looking for more content.

How to Win: The goals for every mission of Andor are unique. From what I can tell from the first two Missions, one common goal will always be to protect the castle. The game has a tower-defense like core mechanic where monsters are constantly rushing towards the castle. It’s really smart, because it gives you a common, shared back pressure.

I found designing Sol Rising that you always want to give your players an amount of grounding so they aren’t shocked when you reveal something else. A new scenario shouldn’t feel like 2.0. More like 1.5, or even 1.3.

In addition, every scenario features a number (2 each, so far) of additional objectives that must be accomplished. In the first mission, a letter had to be picked up and carried safely to the other side of the board. The players had to avoid contact with the enemy while doing so. In the second scenario, I had to find the witch, obtain the herb, bring the herb to the king, and destroy an enemy castle. Again, all of this while protecting the castle from the hordes.

Setup: There is a handy standard setup card where you place the fog, wells, Event deck, and various tokens. The specific scenario will then define where the heroes begin, what enemies are placed, any unique elements (like runes, or destroyed bridges, for example), and any starting items, stats, or gold.

There is a tracker on the right side with letters (A through N). Every scenario comes with a set of big cards with story and scenario details. Tokens are places on defined letters that pair with the cards so that when the marker moves to space C, for example, the C card is read and resolved.

There are 4 heroes, but if you play with fewer than 4, the ones you choose will alter the group. Furthermore, the number of heroes in the game determine how many monsters can reach the castle before you fail, and in my experience, alters the strategy you must employ quite significantly.

Variance: While there are quite a few elements locked in, such as the hugely important story cards, there’s also quite a bit of variance to evolve the game between plays. I’ve played scenario 2 three times now and it’s been quite different each time, not just in the skills employed by my group as we improve, but how the elements panned out during the scenario.

- The Event deck is rather large, shuffled, and only a (small) portion is experienced each scenario. Some of these significantly alter the scenario by decreasing your stats, granting bonuses, or modifying the terrain.

- There are 15 Fog tokens spread across the map. In the second scenario you need to find the Witch in one of those 15 fogs, so where she appears can really change things. Twice we found her near the castle, but the third time she appeared on the other side of the map. In addition, the fog might reveal additional Event cards, bonus Gold, stat bonuses, or even more enemies. What spawns, and where, really changes things.

- Various entities spawn in variable places. Every space is labeled with a number (1-80). For example, the enemy fortress spawned on a space that was 50+1d6. The Crystals spawned at the number of the first die + the number of the second die. The Herb spawned based on 1d6 and a chart reference. The designer used 3 different dice mechanics to add things to the map! He knew he wanted the castle to generally spawn in the second place, hence the light variance of 50+1d6. However, the crystals and herb emerge in dramatically different locations.

- Although the story cards always resolve when the letter space is reached, the timing of that moment being reached can be sometimes controlled by the player. For example, the Prince leaves at Space G on the tracker. Therefore, you might alter your plans to take advantage of his presence before he left. The pawn that moves along the lettered spaces moves every time you defeat an enemy or end the day.

You also have light variance in the form of combat resolution (dice roll), mini-objectives accomplished (not required, but optional to gain bonuses), and things you buy from the merchant, for example.

Conclusion: I find the system incredibly interesting as it combines a fairly rigid structure in the objectives and order of the story cards, but still adds a great deal of spice in the form of Event cards and scattered map elements. I’m very intrigued to see how the system evolves as I’m only on mission 2 and I know it’s probably still lighter on the puzzle nature of things.

So far, this is a really interesting mixture of story-based scenario design with replay variance still in mind.

Mice and Mystics: Hey, let’s play Rat Zelda.

Mice and Mystics is a story driven cooperative game for 1-4 players. The game revolves around short-tactical combat with some strategy in regards to how you build out your party and whether to solve bonus objectives.

How to Win: Most scenarios involve getting from point A to point B, which usually entails 4-5 large square tiles, all of which are double sided. You must defeat all enemies along the way, making this primarily a game about team-based tactical combat. There is often a boss fight, or tough situation waiting for you at the very end (the final tile).

More and more, especially in the expansion, players face more side objectives, like rescuing a friendly peddler from the drain, finding a particular item, or bringing supplies from one place to another.

Setup: The game defines which tiles to use and in what orientation, as in, how they are placed in relation to one another. Typically you’re allowed to pick any four heroes, but sometimes you have heroes that you MUST use, or heroes that you cannot use, plus a few of your choice.

The game will often have you shuffle a set of Event cards that define which enemies emerge, though sometimes the game will tell you to set a specific type and number of enemies on a defined tile.

The game also defines how much time you have to complete the scenario. Some scenarios specify certain weapons to be used by specified characters

Variance: Mice and Mystics is somewhere around Legends of Andor in terms of variance. I find that I don’t often replay missions, as the game is so story driven, except when I fail. In this sense, I think Legends of Andor has a leg up in replay value as it is a bit more system driven.

While individual scenarios don’t have an extensive amount of variance, the variety between scenarios is significant. The designer clearly strove to create a slew of fresh experiences. You can see variance in Mice and Mystics in the form of:

- What enemies spawn as you enter the room. The card will specify which enemies spawn based on what Chapter you’re on. If it’s Chapter 4, something different will spawn than Chapter 2. As your luck and choices change this between missions, it can be significant.

- Combat resolution (roll custom d6). In Legends of Andor, your combat success (for me so far), largely dictates how much time it takes to defeat an enemy, or whether you can defeat them in the current day. For Mice and Mystics, combat goes both ways. An aggressive enemy can deal a lot of damage and convey powerful effects, like webbing, poison, or fire, that will greatly alter things. The mice can have a really bad day sometimes and it’ll alter the game.

- The rate at which the cheese wheel fills up. If the enemies are rolling well, things will escalate quite quickly. Filling the cheese wheel causes a surge, which spawns more, badder enemies, but also decreases the amount of time you have left in the scenario.

- Your success with the Search Action (you need to roll a certain symbol), as well as the quality of items drawn from a rather large deck. Some of the cards, Treachery, will do bad things that have a big impact.

- Which characters you choose can have a dramatic impact. With the base game you have Collin (leader, warrior, balanced), Nez (warrior, heavy offense, bad defense), Lily (archer, ranged, support), Maginos (mage, range, offense), Filch (rogue, heavy offense, good defense, support), and Tilda (healer, decent offense and defense, support). With the first expansion you get another character and the new expansion adds two more. It really changes things and is probably the best reason to replay — can you beat it with x, y, z, and w?

- Choosing a side objective can not only influence the difficulty of the current scenario, but will also dictate choices in later scenarios. Had we not rescued the King in a prior scenario, it would have made a latter scenario much more difficult.

Conclusion: Legends of Andor and Mice and Mystics are both heavily story driven fantasy experiences. There are many comparisons to be drawn. Whereas Legends of Andor’s variance is largely meta, in that it affects the overall scope of the session, Mice and Mystics’ seems to come about in the moment to moment gameplay. Your trip through scenario 2 might feel, overall, the same, but tile 3 might have a dramatically different feel to it between plays.

The combat resolution has a significant effect on Mice and Mystics, which makes sense as that’s the meat of the game. As I’ve said, Mice and Mystics is largely a game about tactical combat. Therefore, the combat effects, attack, defense, health management, and diverse breadth of enemies really shines. I believe strongly that you need to put the majority of your complexity on your game’s primary element. For Mice and Mystics, that’s combat. Therefore, the moment to moment variance is much stronger than its meta-variance.

Robinson Crusoe: This island looks nic — DEAR GOD SAVAGES!

Robinson Crusoe is a cooperative game for 1-4 players that throws them on a deadly island, forces them to find shelter, gather food, invent helpful items, and solve whatever devious problem the game throws at them. I consider it a master worker of scenario design and referenced it (and Mice and Mystics) heavily to design Sol Rising.

The game uses a central worker placement mechanic, heaps of event cards, and a neat dice resolution mechanic to determine precisely how you’ll fail in this notoriously difficult game.

How to Win: I’ve played two of the scenarios and examined a third. Each of them has a completely unique victory condition. In the first, you must gather and set enough wood to create a large signal fire. In the second, you must extinguish the cults throughout the island. In the third, you need to build a boat, find treasure, and, oh, avoid the volcano.

The back pressures for each scenario are identical, plus the occasional twist. For example, you need to eat every night. If you spend the night without shelter, you suffer penalties. There’s always a twist.

Setup: There are a few standards for each scenario, including:

- Shuffle each individual Event deck for gathering food, exploring, etc.

- Choose 1-4 characters, plus Friday and the Dog if you are playing with fewer than four or want to ease the difficulty.

- Place a number of standard inventions (9?).

Then, things change. You create a central Event deck where you draw a very small number of cards from two very large decks. There are approximately 80 cards and you may use 12 or so in a scenario. These have a massive impact on the scenario.

You may be instructed to add specific tiles and items on those tiles on the map. You draw about 6 inventions from a deck to flesh out your total number of about 15 Inventions. The inventions can dramatically alter the strategy you pursue. You draw 2 items that the group shares from a large set.

As I noted above, the victory condition changes with every scenario. Furthermore, there are new rules introduced and the game’s generic tokens (icons) mean different things. The game is a huge sandbox on which the designer (and the community) can create new stories.

There’s quite a bit of variance during setup and with the goals, but most of it comes during the game.

Variance: Dice resolution is by far the most significant contributor to variance in the game. Whenever you take an action without devoting a full day to the work, you must roll 3 resolution dice to see how it went. If you’re building a structure, you roll 3 brown dice. If you’re gathering food, you roll 3 gray dice. There are different probabilities between the different colors. Each die represents something different:

- Whether you Succeed or Fail and gain 2 Morale

- Whether you are Wounded or Not Wounded

- Whether you go on an Adventure

There are quite a few combinations already! In building that structure, you may succeed, take a wound, and go on an adventure. If you go on an adventure, you draw the top card of the specific Event deck. For example, there’s an Event deck for building and a different one for Exploring. This card forces you to make a choice or has an immediate effect. Sometimes they are discarded, but other times they are shuffled BACK into the primary deck to affect you in the future.

Success has huge implications. You may not gather food, which will have consequences at night. You may not invent the Map, which has consequences on your next day’s plans. You may not build shelter, which has consequences at night. Most challenging is that you must choose what to do before you know what will succeed. If you’re confident, you might only have one person gather food. If you’re worried, you may have a guarantee on the food, but then will skip out on doing another action.

In addition to this, an Event card is drawn at the start of every day. These are almost always significant. Furthermore, the deck may contain cards added from the specific Event decks. The game is an ever-shifting mess of quicksand. It’s about risk, careful planning, and a little luck. There’s no Wilson on Ignacy’s deserted island.

Conclusion: There is a relatively simple structure the designer created that allows for nearly infinite possibilities. There is SO much variance in the Event cards, thanks to the combinations of the 3 resolution dice, but also, the sheer variety of the cards.

However, the foundation is where the true variation comes into play. The tokens which contain simple icons allows the designer to affix unlimited new properties to them. The game contains no points or other trappings, but has the same back pressures. This means, like the monsters rushing the castle in Legends of Andor, players have their feet rooted firmly, but the walls can change all around them.

I find the slew of compelling Event content really impressive. There’s so much. I particularly like how the central Event deck grows based on your adventures on the island. But, the framework of unique victory conditions, consistent back pressures, and malleable tokens is where each scenario becomes truly distinct.

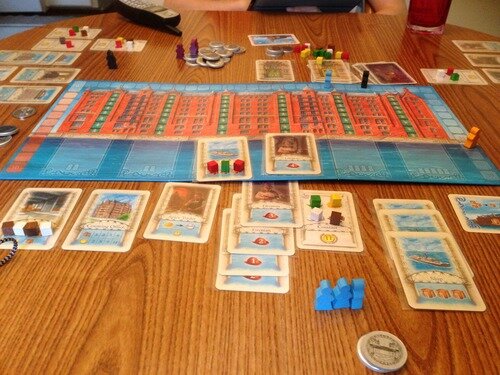

Combat Commander: War is erratic hell.

Combat Commander is a tactical war game for 2 players that tends to take 2-3 hours. It is brilliant for its simple, card-driven play, but also how stories and moments evolve dynamically over the course of the game. This is why the game tends to take a while — things take time to evolve. Small moments need room to grow and breath into epic stories.

As you read the rule book, you’ll find there are only a few paragraphs devoted to telling you how to play. That’s because the game is play a card, do what it says. But, the sheer amount of stuff? Whew. Get ready!

How to Win: The game will sometimes have a victory condition, such as taking an objective before time runs out (or holding that objective). Many include simply having the most points (earned by defeating the enemy and taking valuable ground) when the timer runs out.

Setup: The scenario dictates which Units to use and which map to use (the game comes with 12). You’ll sometimes have pre-defined objectives, other times you’ll draw others that snap into the game quite simply, or may even be private for each player (which is fun). Each player has an action deck of 72 cards, which they shuffle. These action decks are designed for a particular army, so the Italian deck varies from the German deck.

The scenario dictates initial point values, often tied to an objective. For example, the Germans may begin in control of a house that’s worth 15 Points, giving them 15 starting points. It also defines when the scenario ends.

Sometimes the scenario dictates where Units begin on the map, but often, players decide where to place their units within a defined region. This can have an enormous impact on the course of the game.

Variance: Variance for Combat Commander comes as a result of the cards, which dictate everything. On a turn, the active player may only take an action using a card from his hand OR discard cards in his hand to cycle through his deck. This is a key decision and is used often, especially when you have a hand full of Command Confusion cards (dead cards).

The cards have Orders. Each Unit may only take one Order per turn, but you can otherwise play them until you run out of cards. Cards then have Actions, which can be played on your turn OR an opponent’s turn to modify an Order, like firing or movement. An order may be to Move, whereas an Action may be to throw a smoke grenade (to cover that movement) or Opportunity Fire (as the inactive player) to shoot on that Move.

Finally, cards have an Event, which is only triggered when drawn for specific moments, a 2d6 dice roll (which might have an Event), and a hex.

Let’s say you play an Order to attack. To shoot, you tally your attacking Unit’s firepower, then you each “roll” a card by drawing the top card of your deck. You use the dice roll drawn. The dice for either or both of you might have an Event. Let’s say the Event is Sniper! You draw the top card and reference the hex. Any unit on or adjacent to that hex is broken (i.e. wounded). Let’s say the dice just say Event. You draw the top card of your deck, which might say a blaze forms. Where? Yep, draw the next card and reference the hex.

Over the course of the game, a fire may force defenders to evacuate a crucial position. A hero might emerge to charge a machine gun nest. You may stumble across a minefield, or rally broken troops back into the game. Unexpected reinforcements might arrive, or your artillery might break.

The game isn’t about making plans that won’t change. It’s about determining a strategy and dealing with everything that happens along the way. Combat Commander’s victory conditions are dead simple, much like Memoir ’44s, and the rules rarely change. However, the cards create an incredibly broad swathe of possibilities with a gillion different combinations.

So, what did we learn, kids?

Some conclusions one could draw from the previous 4000 words include:

- In scenario design, additional complexity in the form of new knobs and mechanical layers lends itself to greater replayability. In Combat Commander there are dozens of things that can enter and affect the battlefield. In Mice and Mystics, there are tons of new enemies. In Robinson, there are gobs of Event cards and tokens.

- A core rule set that is shared by all scenarios is essential to ground players and also rein in the designer. This goes for both cooperative and competitive, though it’s especially true for the former. In Andor, protect the castle. In Robinson, eat and have shelter.

- Event cards are a fantastic way to add spice and variance to a scenario. However, to keep it thematically appropriate, look to Robinson and Andor, where they have unique scenario cards for each moment.

- Don’t be afraid to add new rules. If you adhere to bullet #2, a few new rules can go a long way towards making something unique. This was a cornerstone of Sol Rising and in testing, it took an hour or less to setup, learn the new rules, and play. It’s possible, just be reasonable.

- Introduce a method of variance for common actions. All of the scenario games listed use dice, or a dice like mechanic to resolve conflict and adventure. All of them give you a slew of cards, be them actions or events.

- Finally, and I’ve said this before, strongly consider the framework of your scenarios. Time invested in the system will pay dividends when it comes time to create content. All of the games above introduce variation and unique moments easily because they have such strong frameworks. If you’re doing it right, you’ll just need to repaint the house and re-arrange the windows for each design. Not start over.

I hope this was interesting and useful. What did you find compelling? Where do you disagree? Was such a deep dive into a single topic fun? Tell all in the comments below!